ASYNCHRONOUS BURST SUPPRESSION IN POST-OPEN HEART SURGERY PATIENTS: ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHIC AND PROGNOSTIC SIGNIFICANCE

Abstract number :

2.147

Submission category :

Year :

2003

Submission ID :

1080

Source :

www.aesnet.org

Presentation date :

12/6/2003 12:00:00 AM

Published date :

Dec 1, 2003, 06:00 AM

Authors :

Peter Widdess-Walsh, Nancy Foldvary-Schaeffer Department of Neurology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH; Department of Epilepsy and Sleep Disorders, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH

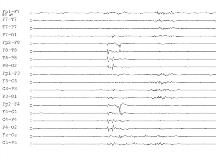

A case series of 4 patients with an asynchronous burst suppression electroencephalographic (EEG) pattern having a [apos]checkerboard[apos]-like appearance is presented. Similar patterns, although not in this setting, have been described in association with traumatic lesions of the corpus callosum (2 cases), severe head trauma (1 case) and in the Aicardi syndrome. The underlying mechanism is attributed to disruption of interhemispheric connection pathways (Lazar, 2000) or damage to temporal-cortical burst pacemaker areas , so-called [quot]one-way asynchrony[quot] (An, 1996). The possible mechanism and prognostic value of this EEG pattern are reviewed.

All 4 patients underwent open heart surgery at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and had postoperative clinical or subclinical focal status epilepticus. None had prior neurological disease. Continuous EEG monitoring was performed in all cases. Three patients underwent pharmacologic coma with pentobarbital. One patient was found to be in burst suppression spontaneously, and was treated with phenytoin and valproic acid for subsequent subclinical focal seizures. All had ischemic infarctions, embolic in appearance, on neuroimaging or at autopsy.

Presumably the underlying epileptogenic lesion was ischemia. In one case, watershed infarcts were also present, suggestive of a diffuse hypoxic-ischemic injury. The average age was 75.5 years. Focal motor seizure activity contralateral to the side of the infarct was seen in all patients. Average duration of burst suppression was 66 hours. In each case, bursts of epileptiform activity in the infarcted hemisphere preceded those seen on the contralateral side. None of the infarcts involved the corpus callosum; therefore the asynchronous EEG pattern cannot be explained by injury to inter-hemispheric connections only. Damage to the burst pacemaker on the side of the infarct or possible release of the cortex from subcortical synchronization may produce this EEG pattern. Two of the patients remained unresponsive and care was withdrawn. The other two patients had prolonged hospitalizations and severe morbidity.

In summary, an asynchronous burst suppression pattern following cardiac surgery was observed in the setting of cerebral ischemic infarctions and was associated with a poor outcome. While the origin of this burst suppression pattern is still unknown, this study suggests that localized lesions in subcortical-cortical pathways interrupt pacing of cortically generated rhythms. [figure1]