Improvement Over Time in Diagnosis of Rare Epilepsy Disorders After Seizure Onset

Abstract number :

2.125

Submission category :

4. Clinical Epilepsy / 4B. Clinical Diagnosis

Year :

2018

Submission ID :

502295

Source :

www.aesnet.org

Presentation date :

12/2/2018 4:04:48 PM

Published date :

Nov 5, 2018, 18:00 PM

Authors :

Barbara L. Kroner, RTI International; Nhan T. Ho, Columbia University Medical Center; Dale C. Hesdorffer, Columbia University; and Brandy E. Fureman, Epilepsy Foundation

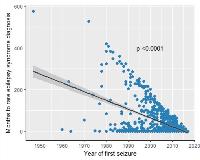

Rationale: The Rare Epilepsy Network is a registry of individuals with a rare epilepsy syndrome (e.g. Dravet) or a rare disorder with a high incidence of epilepsy (e.g. TSC, Aicardi). We sought to determine if there has been improvement in the identification of rare epilepsy syndromes and disorders after the onset of seizures over the past 60 years, or since the syndromes or gene mutations were first recognized as being associated with epilepsy. Delays in diagnosis of a rare epilepsy disorder (RED) may impact prognosis, clinical care, and quality of life for child and family. Methods: Cognitively-able adults and parents of affected children were recruited through over 30 RED advocacy groups. Informed consent and baseline surveys in English were completed through the study website by parents and affected adults. The survey collected information on demographics; seizure onset and characteristics; treatment; RED diagnosis; phenotypes; comorbidities; development; quality of life; and genetic testing. Subjects with missing age at seizure onset or at RED diagnosis or with a diagnosis (e.g. Dup15q, TS, Phelan McDermid) prior to seizure onset were excluded. Analyses included Kaplan Meier curves for time from seizure onset to diagnosis and linear slope of months from seizure onset to diagnosis by calendar year of seizure onset. Separate analyses were run for diagnoses with N>15. Results: Of 1095 subjects with some survey data, 244 (22%) had missing age at seizure onset or at RED diagnosis, and 103 (9%) had a diagnosis before seizure onset leaving 748 (44% males, 56% females) representing 29 specific REDs and 2 broader RED groups included in analyses. Median (quartile) ages at enrollment, seizure onset and RED diagnosis were 10 (5-18) years; 8 (4-24) months; and 36 (1-96) months, respectively. Time from seizure onset to RED diagnosis dramatically decreased (p<.0001) from 1950 to the present (Fig. 1). The relative reduction in time (i.e. slope) by calendar year was similar when the first seizure was febrile (18%) compared to unprovoked (82%), although overall time to diagnosis was longer (p=.005) for febrile seizures. First seizures that were febrile occurred with 14 different diagnoses, although were most common in Dravet (48/105, 46%). Time from first seizure to RED diagnosis was shorter (p=.004) for individuals in foreign countries (13%) compared to the US (87%) [Fig 2], although both had similar reductions in time to diagnosis by calendar year. There were also marked improvements in time to diagnosis over calendar year for TSC (n=121, p=.0002), LGS (n=125, p<.0001), Dravet (n=106, p<.0001), Aicardi (n=57, p=.002), Phelan McDermid (n=16, p<.0001)) hypothalamic hamartoma (n=53, p<.0001), PCDH19 (n=29, p<.0001), CDKL5 (n=23, p<.0001), SCN8A (n=16, p<.004) and all other RED (n=95, p<.0001) or genetic mutations (n=44, p<.0001). Doose (n=40, p=.14) and Dup15q (n=23, p=.75) saw no improvement in diagnosis over calendar time. Conclusions: Virtually all rare epilepsy disorders benefited from improvement in diagnosis over calendar time which may be due to increased awareness of diagnostic criteria, earlier referrals to epilepsy specialists, high resolution MRI, and genetic testing of children with refractory epilepsy. It is not clear why neurologists outside the US (mostly Canada, UK and Australia) diagnosed RED sooner after seizure onset than those in the US. Febrile seizures at onset likely increased time to diagnosis as this is common in young children and clinicians may be more inclined to observe which further delays diagnosis. More rapid and accurate diagnosis of rare epilepsies should improve prognosis by guiding treatment decisions. Funding: Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

.tmb-.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=6310214d_0)